María Eva Duarte de Perón, more commonly known as Evita was born on 7 May 1919, and died of cancer aged 33 on 26 July 1952. We were wondering about the origin of the signature song Don’t Cry For Me Argentina and who was the real Eva Perón?

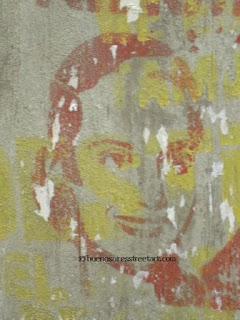

Stencil of Evita in Buenos Aires (photo © BA Street Art)

The song lyrics in Don’t Cry For Me Argentina are openly critical of Eva and her penchant for designer clothes and jewellery with lyrics such as: “All you will see is a girl you once knew. Although she’s dressed up to the nines. At sixes and sevens with you.” Parker’s production is extremely lavish with Madonna holding the record for the most costume changes in a movie – an estimated 85 times (including 39 hats, 45 pairs of shoes and 56 pairs of earrings).

Another song entitled “The Money Kept Rolling In (And Out)” refers to Eva’s charitable work and allegations of money laundering, while also implying that she cultivated a glamourous image to impress the poor people of Argentina and to help promote Perónism. Another song (“You Must Love Me”) suggests that it’s only when Eva realises that she’s dying from cancer does she renounce her pursuit of the vice-presidency and realise that Perón loves her for herself with the words: “How can I be of any use to you now?”

Eva and Juan (photo © BA Street Art)

Desanzo’s film, though much lower budget, focuses on Eva’s political career and last years. It portrays her as a brave, charismatic. passionate woman, and a champion of women’s and workers’ rights. The Eva of Desanzo is conscious of her roots, she is a sensitive, tearful woman with a human touch, holding babies and hugging pensioners. The movie was released while Carlos Menem’s government was in power and is perhaps the reason why there is no shortage of Perónist propaganda.

Esther Goris, who plays Eva, gives a rousing speech at a school that includes the frequent use of the words ‘Peronista’ and ‘Peronismo’ before she had even met her future husband. There is also a scene when she meets Juan Domingo Perón for the first time at Luna Park and flatters him saying that the people call him ‘Colonel of the people’.

The cast and crew of Parker’s movie faced protests in Argentina upon arrival over fears that the project casting The Queen of Pop in the lead role would tarnish Eva’s image. Madonna’s forays into acting had previously included the abysmal erotic thriller Body of Evidence and Desperately Seeking Susan. Indeed she did seem to be making a mockery of Argentina’s most loved lady and many movie critics panned her performance. Eva Perón wasn’t the saint as portrayed by Desanzo, neither was she the star-gazing child who went from slutty gold-digger to talentless actress to wife of the president, as portrayed by Stone and Parker. But Desanzo’s version is a truer reflection of Eva than is so often the case when Hollywood gets its hands on a biographical movie script

Portrait of Eva on the Ministry of Public Works building in 9 de Julio (photo © BA Street Art)

A feature entitled ‘Eva Peron The Myth’ in La Nación newspaper unravels her legacy: “She lives on as a myth with her unique personality that is constantly associated with all political solidarity. Insolent, sarcastic, spiteful, with a natural elegance that chose Coco Chanel when she was advised not to overdress. Born with a thirst for power, she came from humble origins with her surname in dispute (her birth certificate read Duarte while her baptismal certificate read Ibarguren) and achieved a great death that shook the world like a Greek tragedy. Her death was like that of a saint despite the fact she didn’t belong to a religious order.”

Evita mural in Constitución (photo sent in by Delphine Lamour)

Evita mural in Constitución (photo sent in by Delphine Lamour)

Evita also founded the Women’s Branch of the Perónist Party and created the Eva Perón Foundation through which schools were built, nurses trained and money dispensed to the poor. La Nación commented: “The poor people started to revere her like a Mother Teresa with French tailors.”

Eva’s final speech

Some people say Eva was using Perón to get famous and Perón was using Eva to become president. Her final speech from the balcony of the Casa Rosada, as she addressed ‘los descamisados’ (the shirtless ones) while suffering from cancer, was heartfelt and moving. She hated the rich (la oligarquia) and was demonized by the upper and middle classes who frowned on her for her illegitimacy and promiscuous past. She was a populist ‘with a little bit of Robin Hood’, says La Nación. Above all the common people loved her and admired her. Many of them wept in Plaza de Mayo during her speech with the scenes inspiring Rice’s famous song.

Evita addresses ‘the shirtless ones’ (photo © BA Street Art)

“Eva lost all sense of reality with politics,” her friend Father Benitez said about her last speeches. “She felt the pain of another like her own,” wrote Abel Posse in La Nación. “Eva worked for 20 hours but she only understood the power that power gives. She felt democratic, annointed by ‘the shirtless ones’ but she didn’t respect the rules of a republic that ended up being hypocritical… to feel democratic and a missionary was the intolerance of Eva, the source of her obstinate way of seeing things in black and white.”

It was thanks to Evita that Perón won the elections in 1946. She was given a state funeral and mourners turned out in their millions to pay their respects. So overwhelming was the public outpouring of grief that within one day of her death, all the florists in Buenos Aires had run out of flowers. She was considered ‘the spiritual leader of the nation’, and remains a national hero and icon. Her impact on Argentine politics remains huge and graffiti of Eva can be found all over Buenos Aires along with slogans reading “Evita vive” (“Evita lives”). Like Eva herself, her husband also provokes adulation from his supporters and hatred from his detractors in equal measure.

To his followers, Perón and his wife were champions of the poor, the working class and the welfare state. To his critics, Perón was a military dictator, a fascist leader who helped facilitate the sanctuary of Nazi war criminals such as Josef Megele and Adolf Eichmann in Argentina. He also sowed the seeds of economic and social ruin by encouraging the uneducated and ‘the plain lazy’ to live off handouts from the state.

Punk Perón (photo © BA Street Art) |

All photos © Buenos Aires Street Art

For more information about Eva Perón check out the following links

La Nación anniversary tribute in photos

La Nación Eva Perón El Mito (Spanish)

The Washington Post

The Death and Afterlife of Eva Peron

New York Times obituary 1952

One reply on “Don’t Cry For Me Argentina: Eva Perón graffiti”

Claire

I find this article fascinating. I spent a year living in Argentina during my degree, fell in love with Evita (!) and wrote my degree thesis on ‘representations of eva peron in argentine prose fiction’ – I guess just another art form. I did look a bit at iconography as I did a course on portrayals of Evita at the UBA while I was living there.

I don’t suppose you could tell me the artist who did “Evita and the shirtless ones”? I would actually like to use that stencil for something I am planning for my house.

Thanks a lot!

Claire

Comments are closed.